COMMENTARY

For truth, justice, and barbecue

9/11/2017

A sample of chicken for judging portion of the class.

THE BLADE/MARY BILYEU

Buy This Image

LEBANON, Ohio — Two dozen men and 10 women, including me, sat in a conference room at the Miami Valley Gaming casino in Lebanon, Ohio, on Aug. 31. I could hear people chatting about smoke rings and burnt ends: the finer points of barbecue.

But these were not mere barbecue buffs trading techniques for the next backyard grilling session. These were devotees, dedicated to the art of smoked, slow-cooked meats.

We had all signed up for a class hosted by the Kansas City Barbeque Society, an organization with 20,000 members that was founded in 1986 to set rules and regulations for competitions. (It sanctions about 500 events per year.) We were about to spend four hours learning about the highest standards for chicken, pork, ribs, and brisket so that we could become CBJs — Certified Barbeque Judges.

I overheard one man say that he is part of a competitive team and wanted to refine his knowledge of what judges are seeking. Another has been to Memphis in May, an annual festival known affectionately as the Super Bowl of Swine; he and a friend are touring the top 10 rated barbecue events around the country, and he is hoping to judge at some of the contests.

Deb Weiser of Bowling Green said she used to go to a festival in Indiana that hosted a fun barbecue event, and it got her to thinking: “I wonder how you get to be a judge?” So she looked it up and found the organization’s website, kcbs.us, a one-stop warehouse for events, classes, and other pertinent information. She signed up online, paid $115 for the class and a one-year membership in the KCBS, and was ready to learn — and eat, though that part came a bit later.

Steve Grinstead, who has been involved with the KCBS for 21 years, was our instructor. He is a Master Certified Barbeque Judge, a status earned by cooking with a competitive team at least once, serving as a judge at a minimum of 30 events, and passing an online exam. He can’t remember the last time he cooked barbecue, he said, as he judges so many events that there’s no opportunity or need.

A sample of chicken for judging portion of the class.

With a mix of good humor and serious dedication, Mr. Grinstead crammed a dizzying amount of information into the first two hours of the class. There are very specific standards for entries in each of the four KCBS categories, and CBJs are pledged to uphold these expectations even if they contrast with personal tastes.

We learned that a minimum of six portions of food are always presented to ensure one portion per judge at a table, and they are always served in white styrofoam boxes for uniformity and convenience. Sauce and garnish are both optional, and the latter can only consist of green lettuce, curly green kale, parsley, and/or cilantro. But if we eat with our eyes, anticipating an entry that looks enticing, then garnish may earn extra points for appearance. As Mr. Grinstead said, “It’s mental. It’s subliminal.” Visuals count.

Foreign objects, even toothpicks, are forbidden. Mr. Grinstead told of one contestant having snipped off a tiny piece of a purple latex glove, worn for hygienic reasons, while portioning an entry during a competition. The man had to be disqualified for the transgression, however small and unintended. He later laminated the offending piece and now places it in the food prep area of his booth at each barbecue contest to remind him to “check everything” before turning in his entries, Mr. Grinstead said.

After being informed that chicken can be served with or without skin, that ribs can only be pork and that they are overcooked if they fall off the bone (despite this being many people’s preference), and that brisket should be tender enough to pull apart without falling apart, it was time to put our new skills to use with some sampling.

But after two hours of learning protocols, standards, and rules, Ms. Weiser spoke for many of us when she said, “I feel completely underqualified.” The much-anticipated food judging portion of the class — offering two samples each of chicken, ribs, pork, and brisket — suddenly seemed overwhelming.

The chicken thighs that had been glazed with sauce and served atop green lettuce looked enticing. Tender, juicy, and peppery, these earned high marks from me in the designated categories of appearance, taste, and texture: 8, 7, and 8 respectively on a scale of 9 (excellent) to 2 (inedible), with 1 being reserved for disqualification. The second chicken offering was a haphazard assortment with poor flavor, so it didn’t fare as well.

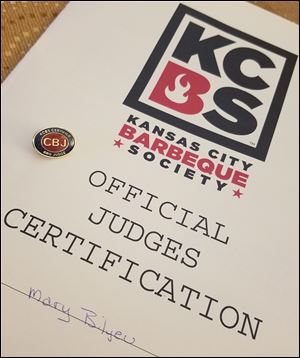

The official KCBS class manual and Certified Barbeque Judge pin.

When we got to the ribs, my table had one portion too few in the first box; that led to all six judges being required to assign a 1 for appearance, with Ms. Weiser, the judge who’d been deprived, required to score 1s across all three categories.

As I lifted a sample from the second presentation box, the meat came up with the fork but the bone was left behind; I scored it only a 3 for being over-cooked. (“I’d be right there with you,” said Mr. Grinstead, if that had happened during an actual competition.) This rib sample also earned a 1 on appearance from all of the judges, just like its predecessor, but for a different reason: red leaf lettuce, a forbidden garnish, had been used.

Neither of the pork samples tasted very good. The first one we were given was perfectly tender, though, while the second was extremely tough.

And finally, the brisket was served. The first option had a bitter aftertaste from too much smokiness; but it still fared better than the second, which was necessarily discounted to a 1 in the appearance category for a pool of sauce, another no-no. Sauces may be served in containers or brushed onto the meat, but a puddle of it is not acceptable.

While it seems that eating your way through a barbecue competition would be akin to partying the day away, the KCBS requires that CBJs sign a pledge to uphold a code of conduct. Treating others with respect, not consuming alcohol or other such substances prior to or during a judging stint, not influencing other judges, and abiding by the organization’s anti-discrimination and anti-harassment policies are mandatory.

The CBJ program is “about joining a fraternity” (and, increasingly, a sorority) “celebrating barbeque,” writes KCBS co-founder Carolyn Wells in her introduction to the judges’ certification manual. The KCBS itself is about food, family, fun, and friends, she continues, and this session certainly was both educational and entertaining.

At the end of class, we all stood, raised our right hands, and swore the following oath:

"I do solemnly swear

to objectively and subjectively

evaluate each barbeque meat that is presented to

my eyes, my nose, my hands, and my palate.

I accept my duty to be an official KCBS certified judge,

so that truth, justice, excellence in barbeque,

and the American way of life

may be strengthened and preserved forever."

Hallelujah. Amen. Now, please pass the barbecued chicken to this brand new CBJ.

Contact Mary Bilyeu at mbilyeu@theblade.com, and follow her at facebook.com/thebladefoodpage, bladefoodpage on Instagram, or @BladeFoodPage on Twitter.