CLIMATE CHANGE: THE IMPACT ON FORESTS

Red flags, alarm bells present in forests of the northeast

2/27/2018

Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge in Maine.

The Blade/Matt Markey

Buy This Image

BENEDICTA, Maine — An autumn drive through the rugged forests of New England and eastern Canada presents a convincing case that this is the place where postcard images are made. The vast stands of brilliant maples, gilded aspens, and papery-barked birches create a striking contrast with the ribbons of deep green hues found in the concentrations of spruces and firs.

To the casual observer, with the northern hardwood forests and the ever-present conifers, Mother Nature has created an unmatched mosaic that likely has been associated with this region of North America for eons prior to European settlement of the continent.

Looking deeper, biologists see red flags and hear the clanging of alarm bells.

“When I see that forest, I see change,” said Justin Richardson, a biogeochemist and assistant professor in the University of Massachusetts Department of Geosciences. “No forest is ever stagnant, and there are always new species moving in and old species moving out, but those changes normally take tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of years to take place.”

Mr. Richardson, who conducted extensive research on the changing climate and its impact on the forests of the region as part of his doctoral work in Dartmouth's Department of Earth Sciences, led a 2016 study that concluded climate change is prompting a makeover of the forests of greater New England.

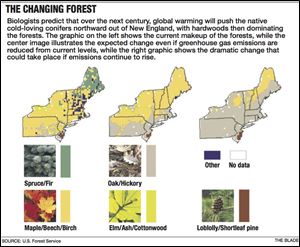

“What we’re seeing now is a much more rapid change,” Mr. Richardson said. “We believe a shift is clearly taking place, from coniferous to more deciduous vegetation.”

The forests of New England and the Maritime provinces of eastern Canada have undergone changes in the past. Large areas were cleared to make way for agricultural use more than a century ago, but the forests regenerated when much of the farming moved westward, where the terrain and weather conditions were better suited for raising crops.

Today, the New England-Acadian woodlands here are a mixture of the hardwood forests and coniferous stands, with loose boundaries between the two. Biologists say that historically, the hardwoods have been the more dominant species in more temperate climate areas, with conifers dominating in the more alpine regions.

“But a changing climate will push certain trees out of the New England region,” Mr. Richardson said. His study concluded that certain climate scenarios project the stands of coniferous trees in that part of the country will lose 70 to 100 percent of their current range to deciduous trees by 2085 because of increased temperature and precipitation, as well as changes in timber harvesting.

Andrew Friedland, a professor in Dartmouth's Environmental Studies Program who was the senior author of the study report, concluded that the changes will not only impact the forests.

"As significant alterations to ecosystems resulting from global change become more likely, environmental scientists and the general public need to appreciate some of the potential outcomes," Mr. Friedland said in the report.

Besides the accompanying impact on the many birds and mammals that utilize this diverse forest habitat, Mr. Richardson said the climate-related change in the forest will likely alter the way the trees in the region cycle nutrients and store toxic metals in their underlying soil, since coniferous trees hold these materials in the ground for longer periods of time.

“Deciduous trees have very different ecological and physical characteristics than conifers, and based upon our findings, we conclude that a shift from coniferous to deciduous vegetation could decrease the accumulation and retention of major metals," he said.

“Looking at the retention of lead in forest soils, from all the lead from gasoline that we burned, forest floors are a sponge for that, but as temperature rises, those materials will leach out. We also expect to have mercury leaching out into the soil, the groundwater, and the surface water, with potentially significant ramifications.”

Keith Ramos, manager, Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge in Maine.

Keith Ramos, manager of the Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge in Maine, shares the concerns about what domino effect climate change might have on the forests and wildlife in the sprawling refuge complexes under his care.

“These are very complex ecosystems that come with a wide range of challenges already, and as we work to protect critically important habitat and properly manage this vast forest, climate change and its impact brings on a whole new set of issues,” he said. “We have to be vigilant and be ready to address new challenges that will undoubtedly come up as a result of climate change.”

Rapid impacts

Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge in Maine.

Some studies predict the transformation of these northern forests could take place at an extremely rapid pace because of increases in mean temperatures and precipitation in the region brought on by climate change.

Daniel Horton, an assistant professor in the Climate Change Research Group of the Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences at Northwestern University, said that while the changes taking place in our forests because of climate change might not be nearly as noticeable as an eroding coastline that threatens to dump dwellings into the sea, the transformations are nonetheless significant.

“Many facets of climate change directly and indirectly influence forests and forest health,” he said. “Increasing temperatures may extend the growing season, shifting pollination and leafing cycles, and potentially exposing trees to more pests and/or pests that are typically only tolerant of warmer climates.”

Mr. Horton said one of the many potential results of changes in our forests brought on by fluctuations in the climate could be a spike in the number and severity of wildfires, something more often associated with the American west.

“Altered precipitation patterns, in particular changes in the frequency and or the severity of drought, may also pose risks for forests,” he said. “Increased evaporation due to warmer air temperatures will lead to the desiccation of forests and their underlying soils and will likely lead to an increase in wildfire risk — a climate change impact that California is dealing with now.”

University of New Brunswick forestry professor Charles Bourque has stated that if greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced, in less than 100 years species such as balsam fir and black spruce could be gone from the region.

"The tree species that require lower temperatures, they will tend to be eradicated form the province of New Brunswick," Mr. Bourque told CBC News.

Studies done by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have concluded that the climate in the northeastern corner of the United States is going through significant change, and the pace is expected to increase in the coming years. The study found that between 1895 and 2011, there was a nearly two degrees Fahrenheit spike in the average temperatures in the region, and projections expect to see that increase jump as high as 10 degrees F in less than 70 years.

The EPA study also revealed that between 1958 and 2012, the Northeast states experienced an increase of more than 70 percent in the number of major rainfall events. That was the highest such acceleration in any region of the United States.

The report also cited the potential loss of economically important tree species such as sugar maple as it moves north into Canada where its preferred climate would be more common. Biologists with the EPA also predict that warmer temperatures will provide a robust environment for outbreaks of pests and pathogens that threaten forest species.

Lyme disease, already on the rise in the region according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, could continue to increase, said Maria Janowiak, the deputy director of the U.S. Forest Service Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science.

“Right now, the biggest concerns for people are the increases in extreme weather events and how those affect road access and also safety,” she said. “But there are a number of other ways that forest changes might impact people — the expansion of Lyme disease and other insect-borne pathogens, since these all interact with warmer temperatures, and create an increased risk to human health.”

Ms. Janowiak said that with forests, the manifestation of climate change is not nearly as dramatic as a wall of ice from a calving glacier crashing into the ocean, but it is definitely taking place. “Over the long term, we expect to see large changes in the composition of forests, but since forests are long-lived, these changes take a long time to play out,” she said. “It can be difficult to see changes in forests in real time.”

Ms. Janowiak added that climate-produced changes in the forests will also have an impact on the wildlife that use that habitat.

“There is definitely a lot of interaction, so with wildlife, it’s hard to know exactly what will happen, since some species will be worse off, and some might do better in a warmer environment,” she said. “Certain species associated with those northern forests, such as the Canada lynx and moose, will be negatively affected by climate change.”

Wildlife changes

The National Wildlife Federation, in its report titled Game Changers: Climate Impacts to America’s Hunting, Fishing and Wildlife Heritage, lists waterfowl and trout as two more likely victims of significant climate change to these forests. The organization states that the northern evergreen forests, primary duck habitat, are being altered by increased fire and pine bark beetle epidemics that result from the more variable climate. Trout become collateral damage since they require the coolest waterways in those forests, and rising air temperatures rob the oxygen from the streams.

Author and birding expert Kenn Kaufman said studies by the U.S. Geological Survey show that several species that rely on spruce and other conifers have been declining in the region, while the same New England region has seen increases in species that prefer a deciduous or mixed forest.

“It's clear that the spruce-loving warblers have declined in New England and the Maritimes,” Mr. Kaufman said, while adding that their numbers could be increasing in the more northern reaches of their range. “The decrease in spruce-loving warblers in the northeast is reason for concern, but not necessarily reason for alarm.”

Mr. Richardson said that as warmer and wetter conditions become more prevalent in the forests of the northeastern United States and eastern Canada, many changes in the composition of those forests, and the impact on the surrounding region, will play out. Trees that prefer warmer and wetter conditions will migrate northward.

“As the climate warms, we expect to see some of the iconic species of New England, like maples and beeches, pushed out. Those will no longer be there,” he said. “We are going to see things we never even thought of — we’ll see a shift in the face of the forests of New England. You can’t change one thing, and expect nothing else to change along with it.”

Contact Blade outdoors editor Matt Markey at: mmarkey@theblade.com or 419-724-6068.