Why to talk about dying

Delaying end-of-life discussions can have serious repercussions

3/20/2017

THE BLADE/JEFF BASTING

Buy This Image

Linda Hanna had some peace of mind knowing she was honoring her husband’s wishes in his final days.

Hal Hanna, who was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, five years ago and died in January, laid out his end-of-life wishes clearly through a living will and health care power of attorney. In the midst of the horrific disease, knowing what he wanted provided a sense of comfort and control, his wife said.

Linda Hanna, whose husband Hal died of ALS earlier this year, sits in her living room and looks at a portrait of she and her husband in Bowling Green on March 16, 2017.

But the Hanna family is in the minority. Few Americans have written documentation outlining their wishes or talked to their families about such decisions. A new study from researchers at the University of Toledo sought to find out why, including why minorities are less likely to have such documents in place. Their findings from a national survey were published in Omega-Journal of Death and Dying earlier this year.

Defining advance care planning as, first, having a living will and, second, having durable power of attorney for health care, and, third, talking to loved ones about end-of-life preferences, the study found 75 percent of respondents had not done so.

Clearly laying out one’s instructions for medical intervention at the end of their life provides family members a guide map and can avoid additional trauma around deliberating or arguing about how to care for the patient, said Timothy Jordan, one of the article’s authors and a professor at the University of Toledo.

“Unless families are prepared ahead of time to talk about this ... you’re sleep deprived, very emotional, not thinking clearly, family members might not agree,” he said of unexpected medical emergencies. The authors’ research found many families risk finding themselves in that situation.

Researchers studied whether behavior models could predict or explain why so few Americans have completed the three steps, he said, and why minorities were less likely to do so.

Breaking it down by race, 33 percent of white respondents had completed such planning, compared with 18 percent of Hispanic respondents and 8 percent of black respondents. As researchers expected, black and Hispanic respondents reported more distrust of the medical system, but that was not statistically significant to explain the disparity, he said.

Minority participants did indicate less overall knowledge about advance care planning. Those with more education and higher incomes were more likely to complete it. And unsurprisingly, those who had been diagnosed with a serious illness or had a relative who had, were more likely to have completed the process.

“A person’s attitudes toward advanced planning was the most powerful indicator,” he said. “It makes me uneasy, fearful … realize my own mortality.”

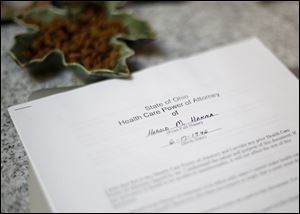

Harold Hanna's State of Ohio Health Care Power of Attorney in the Hanna home office. Linda Hanna said that she would carry this document in her purse in case her husband had a medical emergency.

Still, researchers found that many of the respondents had a positive opinion about making these plans, even if it didn’t push them to actually do it.

“Quite a few people who had positive attitudes toward advance care planning … but when we asked them if they intended to do it, they said no,” he said. “Wait a minute, you had positive attitudes toward it … but when asked if you planned to do, you said no. We began to explore that.”

About three-quarters of respondents said they would complete it if their doctor, or loved ones wanted them to do so.

Regardless of what is holding people back, it’s something every adult 18 and older should do, said Laura Phillips, hospice educator at Hospice of Northwest Ohio and president of the Advanced Care Planning Coalition of Greater Toledo.

A survey of the Toledo-area community in 2006 showed similar compliance numbers to Mr. Jordan’s study, finding a quarter of residents who were hospitalized had completed such directives.

“The concern is that unfortunately we still live in a death-denying society,” she said. “People don’t want to talk about or plan for that time.”

Healthy adults should consider how they would want to be treated in the event of a sudden trauma, such as a heart attack, stroke or car crash, and consider what they would want in terms of artificial feeding, hydration or breathing assistance, she said.

Those directives can change as people get older or are diagnosed with chronic or degenerative illnesses, she said. But filling out paperwork isn’t a stopping point.

“We know that having documents completed does not always make sure your wishes are honored. It’s really the conversations we have with our family and care providers that will provide guidance and assurance,” she said. “Just as we respect people in life, we need to make sure we’re honoring their wishes in that dying process with dignity, respect, and compassion.”

The forms are available online and can be signed by two nonrelative witnesses or a notary. Find the documents for Ohio here: caringinfo.org/files/public/ad/Ohio.pdf. They should be shared with the patient’s physician and appropriate next of kin, Ms. Phillipps said.

As an attorney, Mr. Hanna was well aware of the importance of this documentation, Mrs. Hanna said. Her husband did not want to prolong the disease, and directed he be given no ventilation, hydration, or nutrition.

“It made us feel like we were in more control with what was going to happen; that the medical field won’t take over and have something happen we wouldn’t want,” Mrs. Hanna said. “I kept copies [of the documents] with me all the time, in my purse, in the car, to make sure that his wishes were met, it gave me a little peace of mind knowing that I had that.”

Mrs. Hanna has similar documentation for herself, as do the couple’s three adult children, she said.

For more information about end-of-life planning resources, visit theconversationproject.org or aarp.org.

Contact Lauren Lindstrom at llindstrom@theblade.com, 419-724-6154, or on Twitter @lelindstrom.