Fasting for faith: Abstaining from food offers sense of clarity, clergy say

9/30/2017

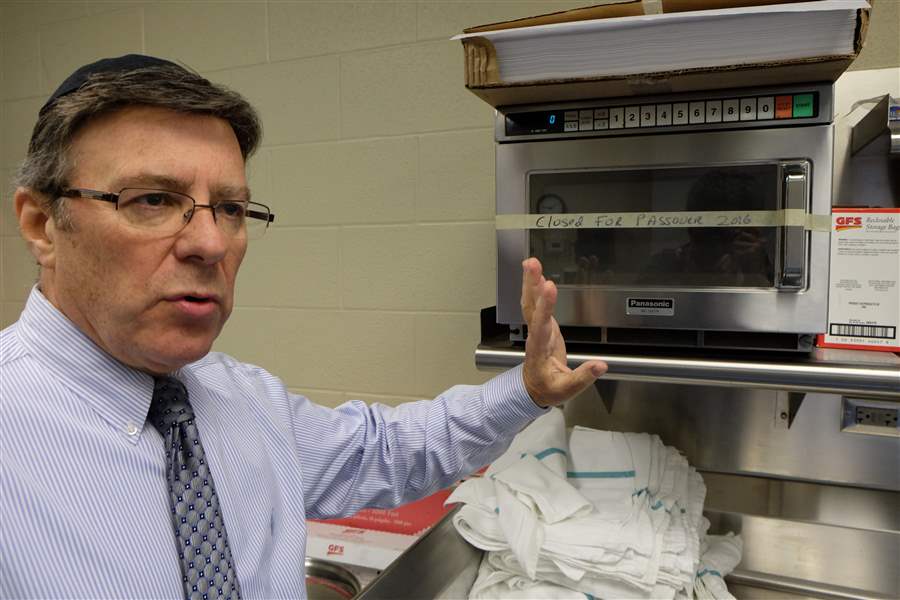

Cantor Ivor Lichterman of Congregation B'nai Israel.

THE BLADE

Buy This Image

Discomfort, to some extent, is an anticipated aspect of Yom Kippur.

The Day of Atonement, as the Jewish high holiday is known, asks adherents to abstain from food and drink in a fast that extends, this year, from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday. It’s a practice that has deep roots in the Torah, which shares text with the Old Testament and which, in a passage tied to Yom Kippur, instructs: “...you shall afflict your souls.”

That’s not supposed to be easy.

“Of course this will be uncomfortable,” said Cantor Ivor Lichterman, who leads Congregation B’nai Israel and described the Jewish fasting practices, which extend beyond food and drink, that today constitute this affliction.

Cantor Ivor Lichterman of Congregation B'nai Israel.

In offering a “return to basics,” he said, fasting does more than bolster the sense of atonement or contrition that is central to Yom Kippur. It also offers those who partake an important opportunity to adjust their focus and calibrate their perspective to “what’s really important.”

It’s an idea that’s shared in a wide swath of faith traditions, including Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, and Hinduism. While the specific approaches vary within each tradition, ranging from the rigid instruction of Ramadan in Islam to the individual preference of upavasa in Hinduism, adherents of each belief system recognize, in some form or fashion, the faith value of consciously foregoing food or drink.

“It’s something that all nations do,” said Imam Brahim Djema, who leads prayers at Masjid Saad Foundation in Sylvania and who pointed to historical ties between fasting in Islam and Judaism.

The precedent for fasting, in most cases, is deeply rooted in religious texts and traditions. Imam Djema cast the sunup to sundown fasting during Ramadan, a holy month on the Islamic calendar, most simply as obedience to a divine command laid out in the Koran. In referencing the Torah, Cantor Lichterman offered a similar explanation within Judaism.

But an empty plate or glass is often in itself is less significant than the heightened consciousness it invokes and the clarity of perspective it brings. This, as well as the related prayer or action that some traditions advocate, is what can deepen a person’s connection to the almighty, according to several religious leaders.

Father James Bacik, a retired priest and theologian within the Catholic Church, echoed faith leaders in several traditions in suggesting that the goal of fasting “is to grow closer to God.”

A closeness to the divine, for example, is a loose translation of upavasa, a Hindu practice that encourages either simple meals or total abstinence, said Pandit Anant Dixit, the priest at the Hindu Temple of Toledo. In contrast to more structured fasting practices that follow religious calendars, upavasa is practiced at an individual’s preference.

The idea is that when someone is not preoccupied by food — preparing, cooking, eating, digesting — their mind can in turn “entertain noble thoughts and stay with the Lord,” said Pandit Dixit, who also cast the practice as a way “cultivate control” over sense and desires.

Other traditions that similarly leave it up to an individual when and how to fast include Buddhism, which emphasizes conscious consumption and mindfulness over extremes, according to Abbot Jay Rinsen Weik of the Greater Heartland Buddhist Temple of Toledo.

And, in some cases, Christians, too, might observe a fast, perhaps under the guidance of a pastor but generally not in line with a religious calendar. Pastor Bill Herzog of Vineyard Church in Perrysburg said he sees fasting as a way to consciously dedicate time and attention to God.

“That’s kind of the odd thing with the name ‘fast,’” he said. “It’s a way for us to slow down.”

Catholics stand out among Christians in adhering to a set of guidelines that, although structured, are notably less restrictive than they were prior to the Second Vatican Council. Father Bacik described a limited fast during Lent: one full meal, as well as two smaller meals, on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, as well as abstinence from meat on these days and on each Friday of the church season that precedes Easter.

Father Bacik, like other faith leaders, described fasting as a practice that can offer important spiritual perspective. And, in some ways, the practice is as much about what Catholics do as it is about what they don’t do. Father Bacik said fasting is necessarily tied to prayer and good works.

Bishop Zach Madden, who leads the Perrysburg Ward of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in pastor’s role, spoke similarly of the spiritual component of Mormon fasts.

“If you fast without praying, you’re just going hungry,” he said.

Church members typically fast on the first Sunday of each month, abstaining from two meals within 24 hours and donating the money they would have spent on food to charity. They might fast outside of that shared monthly experience too, Bishop Madden said. If someone were considering a major career change, for example, or worrying about a loved one’s health, a fast might present itself as a helpful spiritual practice.

“We believe that prayer and fasting go hand in hand,” Bishop Madden said. “Just as you would get spiritual strength from prayer, from that communion with God, fasting is also an act of faith. And by doing that, you can be rewarded by clarity and by a spiritual experience.”

Perhaps the most rigid practices fall under Islam, which classifies the fasting during Ramadan fast as one of its five pillars. But Imam Djema said the monthlong fast should not be seen as punitive.

“It’s something to teach yourself patience,” he said. “When you feel hungry, you remember that many people have no food and are poor. You should be kind to them, you feel their pain.”

“Fasting is a school of good manners, mercy, kindness, patience, generosity.”

Contact Nicki Gorny at ngorny@theblade.com or 419-724-6133.