1st men on moon kept out of each other’s orbit

Aldrin’s visit to Ohio museum an unusual event

8/13/2017

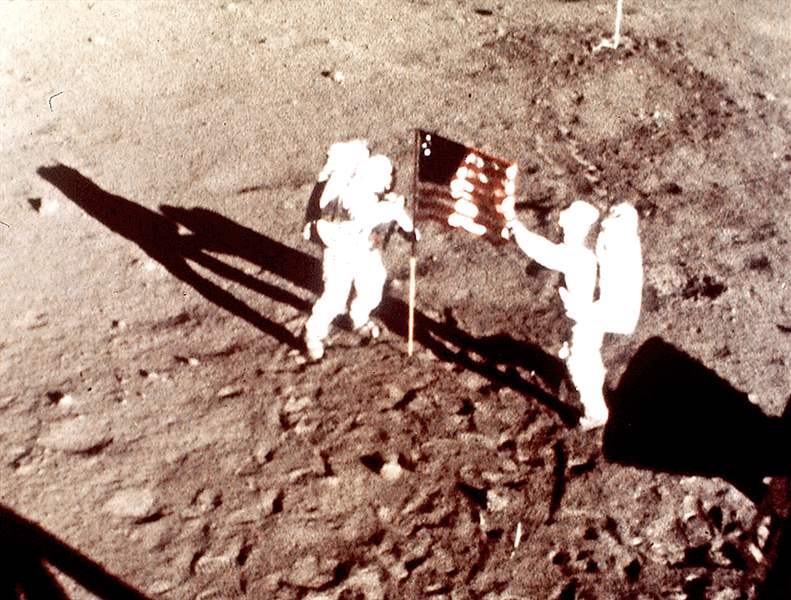

Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin E. ‘Buzz’ Aldrin, the first men to land on the moon, plant the U.S. flag on the lunar surface, July 20, 1969.

NASA

WAPAKONETA, Ohio — The oft-forgotten Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins — who orbited the moon as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to set foot on its surface — has on several occasions called the three members of the historic crew “amiable strangers.”

When asked by historian James Hansen to characterize the relationship between Mr. Armstrong and Mr. Aldrin, Mr. Collins revised his description. “Neutral strangers,” he replied.

There was always a distance between the two astronauts, said Mr. Hansen, who wrote the seminal biography of Mr. Armstrong.

Their relationship was dotted with tension and disagreement — over the difficulty level of training simulations to prepare for Apollo 11, over who would take the first step on the lunar surface, and over the proper amount of public engagement for the first men on the moon.

But last month, just shy of five years after Mr. Armstrong’s death at age 82, Mr. Aldrin paid a visit to the Armstrong Air and Space Museum in Mr. Armstrong’s hometown of Wapakoneta.

There, he headlined the annual Summer Moon Festival, a celebration marking the moon landing’s 48th anniversary and, above all, honoring Mr. Armstrong.

Mr. Aldrin, now 87, spends much of his time on tour. Rarely, though, does he visit a town like Wapakoneta, a rural community of fewer than 10,000. His prior three engagements were at the Kennedy Space Center, the Beijing International Convention Center, and the Giardini Di Porta Venezia, in Milan.

“This was an unusual appearance,” said Christina Korp, vice president of Marketing, Media and Business Development at Buzz Aldrin Enterprises. “I’ll tell you that we don’t usually do events in small towns like that. We did it as a favor to the Armstrong Museum.”

The event will be one of Mr. Aldrin’s last public speaking engagements, Ms. Korp added.

Mr. Aldrin’s appearance in Wapakoneta is even more unusual given his distant relationship with Mr. Armstrong.

Most astronaut crews develop good rapport, NASA astronaut Michael Gernhardt told The Blade. Mr. Gernhardt was especially close with the crew of his first spaceflight in September, 1995. The crew members referred to themselves as the dog crew, threw parties together, and blasted music in their custom-painted 1979 Pontiac station wagon — which they dubbed the dog mobile.

Astronaut-turned-artist Alan Bean of the Apollo 12 mission even did a series of acrylic paintings titled Buddies Forever depicting his crew’s moonwalk.

“I don’t think you could use the phrase ‘amiable strangers’ with any other of the astronaut crews,” Mr. Hansen said.

Certainly, Mr. Aldrin and Mr. Armstrong’s relationship was not standard, especially for two people forever bonded together in history. Their friends, colleagues, and even acquaintances have remarked on their stark contrast in manner and temperament.

Chris Burton, executive director of the Armstrong Air and Space Museum, said he was struck by their distinct speech patterns and fashion senses.

And Allan Needell, a curator responsible for the Apollo artifacts in the National Air and Space Museum’s space history division, recalled having to “drag” Mr. Armstrong to come speak there. Mr. Aldrin, on the other hand, was always up for a public appearance.

“[Neil] was sort of your classic introvert,” former NASA chief historian Roger Launius said. “Buzz is an extrovert. If there’s a camera anywhere, he wants to stand in front of it. And after the camera, wherever there’s the biggest party, that’s where he wants to be.”

Mr. Aldrin and Mr. Armstrong were not friends, Mr. Launius said; they were co-workers. Even during his remarks before a packed house at Wapakoneta High School last month, Mr. Aldrin referred to Mr. Armstrong as his “commander.”

After the Apollo 11 crew parted ways, the two hardly kept up a relationship at all. Mr. Aldrin would sometimes call the far more private Mr. Armstrong to encourage him to participate in public events. Mr. Hansen suspects that Mr. Armstrong rarely, if ever, called Mr. Aldrin.

In a 2009 interview with The Telegraph, Mr. Aldrin expressed regret that he and Mr. Armstrong “hardly [communicated] at all” in their later years.

“I’d rather it be otherwise, yeah,” he said. “It just doesn’t seem proper any more for me to ask him to come to things I’m involved in. And he doesn’t ask me. He doesn’t let me know what he’s doing.”

Mr. Hansen does not think the feeling was reciprocal.

“It’s obviously something that [Buzz] felt,” he said. “I don’t think you’d ever hear Neil say that. I don’t think Neil cared to be any closer to him than he was.”

In Wapakoneta, Mr. Aldrin spoke sparingly of his fellow moonwalker. At a morning road race, he praised Mr. Armstrong’s prowess as an aviator and, in his afternoon presentation, shared a lighthearted anecdote about Mr. Armstrong’s agility on roller skates.

Mostly, though, Mr. Aldrin spoke of his own experiences as a pilot and vision for the future of space exploration.

At least in part, Mr. Burton saw the visit as an opportunity for Mr. Aldrin to learn more about a man he’d regretted not knowing better.

“He and Neil were not that close,” Mr. Burton said. “I think it is kind of an interesting opportunity for him to discover Neil, to find out Neil’s story — what made Neil Neil.”

Mr. Aldrin ate lunch at Mr. Armstrong’s childhood home and dinner at the museum. At the Armstrong House, Mr. Aldrin offered some remarks, but organizers would not give The Blade access to the private event. Mr. Aldrin was not made available for comment.

For Mr. Hansen and Mr. Launius, the visit was a noble gesture to an American hero.

“First and foremost, it’s an opportunity for Buzz to pay homage to a legend,” Mr. Launius said. “Buzz is a legend in his own way as well, but he wasn’t the first man on the moon. And this I think is a classy thing for him to do.”

Mr. Aldrin had never visited Wapakoneta before. It was uncharted territory. And for one of the first two men to walk the moon, that’s saying something.

Contact Jacob Stern at jstern@theblade.com or 419-724-6050.